“Things That Are Survival for Us”

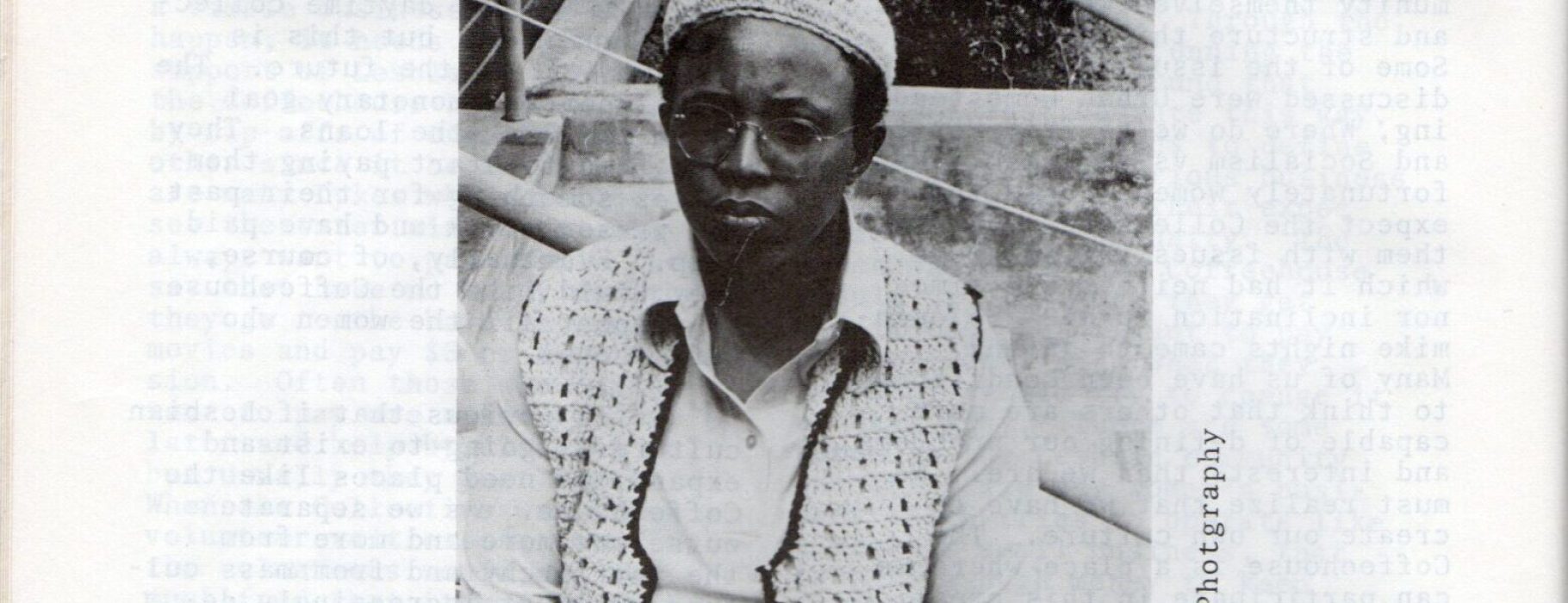

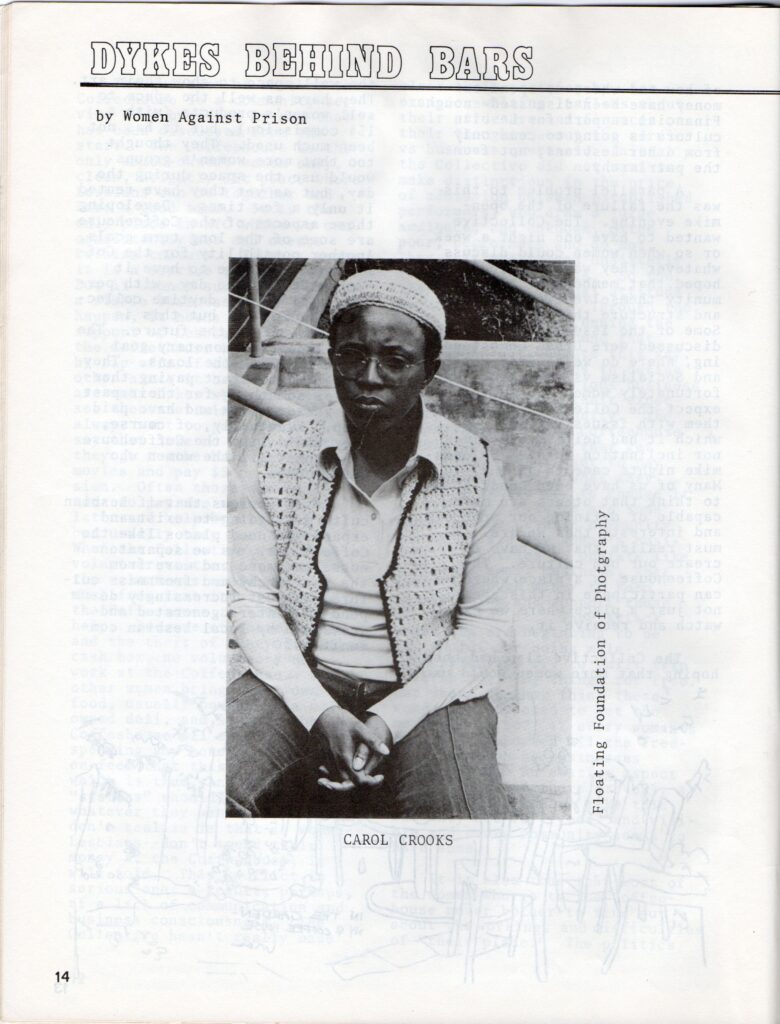

Carol Crooks and the August Rebellion

August 29, 2025

We on the revolutionary left in the United States are inclined to interpret history through icons. Che, Assata, George Jackson, Fred Hampton, Malcolm, Marx: one look at their familiar images and we know what time it is.

But you don’t have to be an icon to be part of history; you don’t have to be in a famous underground cadre, or be martyred by prison or COINTELPRO. You just have to be one person, however “obscure.” You have to stand up for the people you love, to help them live. Then you keep working and fighting. That’s it. Everybody has this potential. And, given history, Black women tend to have it more than most.

Carol Jean Crooks was a Black dyke. Born October 12, 1946, she grew up on the streets of Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, and died alone in early 2022. She worked and fought all her life in relative obscurity. Though most of her work wasn’t legal, her fights created a better and fairer world. If you knew her at all, you probably knew her as Crooksie.

In the early 1970s, Crooksie unwittingly shared space with icons-to-be when she became lovers with, and later a longtime friend of, Afeni Shakur, a brilliant and highly publicized member of the Black Panther Party. A few years later, on August 29, 1974, Crooksie became a small part of recorded history—three years after the Attica Prison Revolt—as the catalyst for the August Rebellion at the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility, where incarcerated women took over the institution and held it for hours. The August Rebellion remains one of the most resounding uprisings in the history of US women’s prisons; it generated a precedent-setting class action lawsuit whose ruling continues to safeguard the right of due process for people imprisoned in New York State, as well as nationally. What follows is a small, incomplete glimpse into Crooksie’s life, taken mostly from second- and third-hand sources. She deserves more, but for now…

“Things That Are against Society but Are Survival for Us”

Crooksie grew up in a world that was bleak and often brutal, but not unusual for a Black child born in the mid-twentieth-century United States. In 1974, while inside the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility for Women, she described to a reporter for the Patent Trader, an upstate weekly newspaper, how she and her younger sister grew up in a one-room basement apartment in Bed-Stuy.1 Barbara Whitaker, “A Venerable Paper Ends a 50-Year Run,” New York Times, February 4, 2007, nytimes.com/2007/02/04/nyregion/nyregionspecial2/04wenoticed.html.

The girls rarely saw their mother, who worked in a factory, then went to night school to become a beautician. Once, when Crooksie was very little, she told the reporter, she got lost in Coney Island and ended up in a police station, happily eating the ice cream given to her by the nice police officers who also let her play with the office equipment. But, as she grew, she inevitably started to see that these cops were beating up Black men: fathers, brothers, uncles of her friends. “It brought hate,” she said. “We started throwing stones at police cars.”2 Joan Potter, “Inmate’s Story: Theft, Fights, Frustration,” Patent Trader, July 6, 1974, available at chappaqua.advantage-preservation.com/viewer/?k=carol%20crooks&t=29861&i=t&d=01011973-12311974&m=between&ord=k1&fn=patent_trader_usa_new_york_mount_kisco_19740706_english_43&df=1&dt=10.

Without a father at home, she realized early on that it was on her, a “little tomboy,” to take care of her mother and sister. So at 8 years old, she started doing odd jobs for a woman who ran a neighborhood rummage shop. “When I started getting into trouble was when people started bothering my sister,” she remembered.

Soon she was on the street, where local gangs hung out and fights happened, where “fast people,” like pimps, would give the kids $10 and tell them to go to a show while they went to work. By the time she turned 11, Crooksie had learned to gamble, shoot craps, play cards. “I would hang out with a whole bunch of boys,” she said, “It was like a family…but no sexual intercourse or anything.” With their mothers out working, the kids generally got only one meal a day at home, usually “a bowl of cornflakes. We didn’t see food again until nighttime.” At night, they’d wait until late, then rob the fruit store or the meat market. “If we stole, it was never for profit, just so we could eat.” She got good at hustling, at “things that are against society but are survival for us.”

Crooksie was around 14 when she was arrested for shoplifting. She was sent to a youth house in the Bronx, where it was clean and there was always food. She wanted very much to stay. Instead, she was sent to King’s County Hospital for psychiatric observation, a place where she saw kids as young as 4 years old “eating their own waste…some talking to themselves.” When they tried to send her home, Crooksie refused. Demanding to go back to the youth house, she set fire to the bedsheets and was taken to another part of the hospital. Here, because she refused to undress and put on a gown, she was given an injection of something and woke up in the psych ward, tied to the bed. After this, the city sent her to an upstate “training school,” where she continued to learn about drugs and prostitution. She remembered the staff making her wear “whorish makeup” and being beaten if she didn’t follow orders. “Up there,” Crooksie said, “the house mothers and fathers can do anything they want to you.”

Eventually, she was allowed to return to Brooklyn and high school. But she got kicked out of school, went back to the streets, and started selling “smoke”—seventy-five cents a stick, and “I could keep twenty-five cents.” The risks got bigger and she got more involved. Finally, in 1965, she was sentenced to three years and sent to Bedford Hills. Not that prison was ever easy, but when 19-year-old Crooksie hit Bedford, she considered it, compared to the institutions she’d already known, “elementary.”

Women’s House of D

Crooksie served her time and went back to New York City just as the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense had begun galvanizing Black communities across the country with its “Ten Point Program” for justice and equality. It was also lighting up the mainstream news media, which focused way more on Panther shootouts, orchestrated by police, than on the Panthers’ free breakfast programs. Damned by the FBI’s J. Edgar Hoover as “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country,” the Panther Party incurred vicious retaliation from government and law enforcement.3 “J. Edgar Hoover: Black Panther Greatest Threat to U.S Security,” UPI, July 16, 1969, upi.com/Archives/1969/07/16/J-Edgar-Hoover-Black-Panther-Greatest-Threat-to-US-Security/1571551977068.

Often, this retaliation was as flagrantly absurd as it was vicious. One egregious example of absurdity was the case of the Panther 21, in which the New York City Police Department (NYPD) figured it was reasonable to concoct a terror campaign that targeted department stores, police stations, railroad lines, the Queens Board of Education building, the Bronx Botanical Gardens—and then charge selected people in the New York Panther chapter with conspiracy to blow them all up. On April 2, 1969, the NYPD conducted a predawn raid, breaking into homes and throwing some twenty-one young Panthers into jail.

The nineteen Panther men were taken to the Tombs, a city jail in lower Manhattan. The two women in the case, Joan Bird and Afeni Shakur, ended up in Greenwich Village, at the Manhattan Women’s House of Detention, where Carol Crooks also happened to be doing time. Crooksie might not have paid much attention to news stories about the Black Panther Party, but she definitely noticed Afeni Shakur.

Hugh Ryan—whose book The Women’s House of Detention: A Queer History of a Forgotten Prison is a radical joy to read—was able to interview Crooksie in 2020 and record her first impressions of Afeni.4 Hugh Ryan, The Women’s House of Detention: A Queer History of a Forgotten Prison (New York: Bold Type Books, 2023). Deft organizer that Afeni was, Crooksie remembers that she would discuss “whatever we asked about” with the women and trans people in the House of D. “She explained to us what [the Panthers] were fighting for.… She had a smile, she was very, very soft in her manner, and everybody did everything for her.”

According to Ryan, the House of D “helped make Greenwich Village queer, and the Village, in return, helped define queerness for America.” The Women’s House of D, besides being yet another grimy, soulless detention center in New York’s law enforcement system, was located on Christopher Street in the Village. If you looked west, through the smudged institutional windows, about five hundred feet away, you could see the Stonewall Inn, the local bar—and refuge—for Village queers.

…the House of D “helped make Greenwich Village queer, and the Village, in return, helped define queerness for America.” The Women’s House of D, besides being yet another grimy, soulless detention center in New York’s law enforcement system, was located on Christopher Street in the Village. If you looked west, through the smudged institutional windows, about five hundred feet away, you could see the Stonewall Inn…

Almost three months after Afeni arrived at the House of D, Stonewall exploded. Beginning in the wee hours of June 28, 1969, as the cops started to load “perverts” into a police wagon, an ad hoc assortment of queers, sick of NYPD raids, harassment, and arrests, decided to fight back. They started by throwing bottles at the cops, igniting a series of riots that lasted five days. Ryan interviewed some of the queer women who lived or worked in the Village at the time. They remembered hearing calls coming from the House of D, “maybe hundreds of voices,” demanding “Gay rights! Gay rights! Gay rights!” and seeing “burning things” floating down from the windows. History will never tell us just what Crooksie or Afeni might have done to help all this along, but it’s nice to imagine. The Stonewall Rebellion may well have influenced Afeni to build more direct links between women’s liberation and radical gay politics, specifically the new Gay Liberation Front, and the Panther program. Interestingly, Panther leader Huey P. Newton did much the same from the West Coast, wondering in a 1970 letter, “maybe a homosexual could be the most revolutionary…”5Huey P. Newton, “A Letter from Huey to the Revolutionary Brothers and Sisters about the Women’s Liberation and Gay Liberation Movements,” Black Panther, August 21, 1970, available at libcom.org/article/womens-liberation-and-gay-liberation-movements.

Meanwhile, the New York Panthers and their support teams needed their best spokespeople out of jail ASAP to argue on their behalf. Afeni, no surprise, was first on their list to get bail, and though her bond had been set at $100,000 (equivalent today of over $828,000)—as it had been for most Panther defendants—she was able to leave the House of D early in 1970. But before she left, Crooksie gave her the contact information for her mother and coordinates for various hangout places in Brooklyn.

The Panther 21 case went to trial in 1970. For its time, it was the longest and most expensive trial in New York City history.6Catherine Breslin, “One Year Later: The Radicalization of the Panther 13 Jury,” New York Magazine, May 29, 1972, available at books.google.com/books?id=4-YCAAAAMBAJ. Finally, on May 12, 1971, in a rapturous defeat for the NYPD, it took the jury no more than ninety minutes—basically, over lunch—to exonerate each and every Panther defendant, even the two who had fled the country. By that time, Afeni had become heavily pregnant. Celebrating the Panther victory, she came looking for Crooksie, who by then was also out. They began a romantic relationship, which inspired Afeni to announce to the world, and the Panthers, that Crooksie was the father of her unborn child.

When the baby was born, on June 16, 1971, the two women named him Lasane Parish Crooks. “He had my last name,” Crooksie told Hugh Ryan. “When the nurse brought the baby in, ’Feni said, ‘Don’t pass him to me; pass him to Crooksie.’” Some months later, various Panthers probably had something to do with renaming the child Tupac Amaru Shakur.

Afeni, though from a similar background as Crooksie, was far more politically engaged and involved in Panther work. Crooksie told Ryan that Afeni tried to persuade her to hang out with the radical gay movement: “She wanted me to come out and do speeches.… I still wanted to make money.” Crooksie did make money, and gave Afeni’s causes a fair amount of it. But she hung back from the Panther limelight, she said, partly afraid of further discrediting the movement with her record of drug dealing.

Criminals Who Make Movements Work

There is a long history of complicated, sometimes tragic, interactions between drug-dealing networks and antiracist revolutionary groups like the Black Panther Party. Panther ideals included ridding communities of drugs and drug dealers; yet some of the Panthers or the people they were close to were, themselves, dealers or addicts. As much as political people like Newton sincerely wanted liberation for Black people, the communities in which they lived were often enmeshed in the drug world. And anyone who’s heard Tupac’s song “Dear Mama” has heard about Afeni Shakur’s addiction.

Paul Coates has thought long and hard about this. Coates joined the Baltimore chapter of the Panther Party in the late 1960s, and started the Black Classic Press in the ’70s, partly to help fellow Panther Eddie Conway survive and organize through forty years of prison. Panther membership included middle-class college students, plumbers, and professors, recalls Coates in The Brother You Choose, my book about his friendship with Conway.7susie day, The Brother You Choose: Paul Conway and Eddie Coates Talk About Life, Politics, and the Revolution (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2020), haymarketbooks.org/books/1466-the-brother-you-choose. There were Panther “saints,” says Coates, but

there were also some cold-up criminals. But could any revolutionary group be other than that? I mean really, quote-unquote “revolutionary”? It takes your criminals; it takes your college students, and it takes those people who feasted on their own people. That’s how they rose; that’s where they come from. That’s how you would explain Huey P. Newton. He was not above that, but he put things into a political context. I got that. But I don’t know if he’s so different from other criminals who have made movements work throughout the world.

Crooksie was never a Panther, but she was an intimate part of this world. After she and Afeni broke up, according to Ryan, Crooksie stayed a part of Afeni’s life for years and she was close to Tupac until his death in 1996. Afeni went on to live a varied and complicated life, becoming involved with the South Bronx Lincoln Detox Clinic and Mutulu Shakur, with whom she had a daughter, Sekyiwa. One of her jobs, early on, was as a paralegal at Bronx Legal Services. It was here that she played a major role in keeping Crooksie alive.

Unmentioned in the local news was Black Solidarity Day, a Bedford event that took place in November 1973. Crooksie, with the help of Afeni and Jan Smith (who later became Yaasmyn Fula) at Bronx Legal, organized this event for family and friends of the incarcerated Bedford women. It might have been this occasion—less publicized and more political—that had something to do with what the prison staff did to Crooksie early the next year.

Powell v. Ward

On February 3, 1974, Crooksie complained of a throbbing headache and asked to see a nurse. A female guard told her she would have to wait until that night. Crooksie pushed past the guard, who decided that Crooksie had assaulted her. She called four other female guards to help subdue her. A battle ensued and, seeing that Carol Crooks was winning it, Bedford’s warden Janice Warne called in male guards from the nearby Green Haven and Sing Sing correctional facilities for men. Several guards soon arrived at Bedford and began the beatdown of one woman who was barely five feet tall.

Eight of the armed males went into Crooksie’s cell and beat her bloody with clubs and belts, then wrapped a sheet around her head and a towel around her neck and dragged her by the neck across the prison courtyard in full view of the other inmates.… They took her in that manner to segregation (solitary confinement) and ordered her to strip naked in front of them. She refused.… They then threw her down and pulled her clothes off and threw her naked into a stripped cell (…no toilet, no sink, no bed or blankets…) They left her naked…in the dead of winter with the windows opened for three days.… On the fourth day, a nurse…found that Crooks had to have an operation on her knee due to the beating.

While holding Crooksie in solitary confinement, the New York State Department of Corrections convicted her of three felony assaults and added two-to-four more years onto her sentence. Meanwhile, Stephen Latimer, a dedicated attorney at Bronx Legal, assembled a team and brought to court Carol Crooks v. Warne.10Crooks v. Warne, 516 F. 2d 837 (2d Cir. 1975). In July, the court ruled in Crooksie’s favor. Five months after her beating, she was finally released from the hole. From now on, Carol Crooks—and presumably, all women at Bedford Hills—would be entitled to formal, written charges before being sent to solitary.

Only a few weeks later, on August 28, an incarcerated woman accused Crooksie of hitting her in the mouth. As if the Crooks v. Warne ruling had never happened, the prison again ordered Crooksie into solitary confinement. But Crooksie stood up and, drawing on the legal victory, demanded to be formally presented with the charges against her. This occasioned five female and six male guards (again imported from Green Haven and Sing Sing) to beat and humiliate her in much the same way as they had six months earlier. This time, however, they also threw her down half a flight of stairs, in full view of Sid Reed and many of the women.

On the morning of August 29, Reed, with several other women, arrived at the warden’s office, demanding that Crooks be released—and to know if she was still alive. They were told they’d get their answer by 6:00 p.m. that day. By 7:00 p.m., with no answer and no sign of Crooksie, the women were ordered to lock down in their cells.

Years later, in a 2016 article for the Village Voice, Reed told journalist J. B. Nicholas what happened.11J. B. Nicholas, “August Rebellion: New York’s Forgotten Female Prison Riot,” Village Voice, August 30, 2016, villagevoice.com/august-rebellion-new-yorks-forgotten-female-prison-riot. As things were heating up, Reed remembered, there was a Black woman guard, “more of a motherly type than an officer,” who, seeing that the women were fixing to riot, tossed the keys to them and ran out the other way. And so began the August Rebellion.

Descriptions of the rebellion differ, depending on the source. Some forty-five, or seventy, or two hundred, or more desperate and infuriated women fought the prison administration for hours—two and a half, or four, or maybe more. They snatched sets of keys, streaming from floor to floor, then building to building, opening cell doors. As a captain threatened to call the National Guard, Reed remembers, the women refused to move. So the cops brought out the water cannon. “They water-hosed us for quite a while, then they threatened to shoot teargas,” Reed told the Voice. Finally, the women decided to stop, “so we just peaceably put our hands behind our heads and everybody just marched back to where they were supposed to be.”

Descriptions of the rebellion differ, depending on the source. Some forty-five, or seventy, or two hundred, or more desperate and infuriated women fought the prison administration for hours—two and a half, or four, or maybe more. They snatched sets of keys, streaming from floor to floor, then building to building, opening cell doors. As a captain threatened to call the National Guard, Reed remembers, the women refused to move.

But they still didn’t know if Crooksie was alive or dead—until a day or so later, when some of them, as punishment for rebelling, were sent to solitary. There Crooksie was, Reed remembered. “Still half-dead, moaning, groaning—I don’t even think at this point she had gotten any medical attention.” A few days after the rebellion, the Patent Trader interviewed Janice Warne about “the inmate whose punishment set off the…insurrection.” Warne told the paper that Ms. Crooks “was well aware” that she would be sent to “segregation,” but “she chose not to conduct herself like a lady.”12Joan Potter, “Prison Quiet, Inmate Moved,” Patent Trader, September 5, 1974, available at chappaqua.advantage-preservation.com/viewer/?k=carol%20crooks&t=29861&i=t&d=01011973-12311975&m=between&ord=k1&fn=patent_trader_usa_new_york_mount_kisco_19740905_english_48&df=11&dt=20.

In 1975, Dyke Quarterly also reported on the aftermath of the rebellion. There were twenty-eight women thrown into solitary, while twenty-five were sent to the prison hospital for treatment of their injuries. Some days later, guards informed Crooksie, in solitary, that her mother had come to visit her. Crooksie left with the guards—who took her, with seven other women, north to the Matteawan Hospital for the Criminally Insane. This institution turned out to be essentially a dumping ground for nine hundred men, also deemed “criminally insane.”

Judging from Dyke Quarterly, the rebellion seems to have continued in small ways. When, for instance, the State Corrections Commissioner Benjamin Ward came to Bedford in 1975, he asked some of the women there, “What if I got some guards to hold Carol Crooks down, would you like to beat her ass?” The women told him that they would instead prefer to beat his mother’s ass. (Ward was to become the first African-American Commissioner of the NYPD, from 1984 to 1989.)

Back at Bronx Legal, Latimer and the staff were not done. This time, they launched a class action lawsuit, Powell v. Ward.13Powell v. Ward, 643 F. 2d 924 (2d Cir. 1981). More comprehensive and thorough, the suit took eight years to win, but ultimately, an out-of-court settlement at the Second Circuit US District Court guaranteed due process in a prisoner’s internal disciplinary proceedings, including the right to know the nature of the charges, to call witnesses, to get a written decision, and, if convicted, to be placed in solitary for no more than seven days. The settlement also succeeded in replacing several of the Bedford Hills staff and ruled that only prisoners who were certifiably mentally ill could be sent to psychiatric facilities. On top of that, in 1981, the court awarded the women of Bedford $127,000.14Tessa Melvin, “Fund for Inmates Celebrated,” New York Times, June 26, 1983, nytimes.com/1983/06/26/nyregion/fund-for-inmates-celebrated.html.

Two Close-Ups of Crooksie

Roz: “I Deserve What Everybody Else Is Fucking Getting”

Rosalind Smith (Roz)—now a community leader for Release Aging People in Prison (RAPP Campaign)—spent time in Bedford Hills with Crooksie in the early 1980s. Roz remembers that settlement well.

It was major. That lawsuit created due process in our tickets when we went to disciplinary. It created an oversight of the medical department. With that money, we were able to buy washing machines and dryers for the unit, ice machines. We got our library stocked with African American and Latino books. Our law library was upgraded.

And, in 1983, with the last of that settlement money, Crooksie organized a big ice-cream picnic—an event that somehow got noticed by the New York Times. “Sometimes,” Crooksie told the Times, “prison inmates and officials can sit down at a table and settle things without rioting.” A few months later, Carol J. Crooks, having served her time, walked free out of Bedford, never to return.

Roz remembers living in the same unit with Crooksie.

She wasn’t a big person, maybe five feet, and she had the smallest little teeny feet, size three or four; crusty, a lot of built-up calluses. You look in the shower: “Oh, that’s Crooksie.” She wore thick Coca-Cola glasses; her eyesight was bad. She didn’t talk a lot, but when she did, she got those motherfuckers in the prison to listen.

I ask Roz if, over the past decades, Bedford Hills has improved.

After Crooksie won that lawsuit, the political climate changed, things weren’t as agitated as before. Things started swinging towards, “Let’s help marginalized communities. Let’s give access to college…” But it’s still fucking prison. The officers still train other officers to think: These prisoners are gonna lie to you, manipulate you; they’re lower than the scum of the earth. They tell us you’re here because you are a piece of shit, and we’re here to correct you.

I wonder if, maybe because of her contact with the Panthers, Crooksie ever called herself a revolutionary.

She didn’t really talk like that. She didn’t talk a lot, but when she spoke, she spoke with purpose. Because she had to fend for herself so young, I think she always had some kind of knack for what was right. She taught herself to think like: I deserve this. I deserve what everybody else is fucking getting, and I’m gonna fight for it. It wasn’t a lot of bullshit with her. She really was a boss.

So she was well liked?

No. Not everybody liked her. But everybody respected her. Whether it was selling drugs or running the prison music room or fighting for her and everybody’s rights, she took everything seriously. It’s not about her being a hero. It’s about her being in a place that was so desolate and dark and demonized that she was…the rose that broke through the concrete.

And, by the time the class action was settled, according to Roz, Bedford had given Crooksie

carte blanche. She pretty much ran the prison. She ran most of the programs. We used to have skating inside; she ran that; she orchestrated the events. She would call me into her cell. We’d smoke weed together. We would drink.

I ask Roz how Crooksie lived after she got out.

She was a drug dealer, honey. She was ruthless, but she also cared about the community.

Mel: “She Took Me Under Her Wing”

LaMelle (Mel) Smithers is a social worker at Montefiore Hospital in the Bronx. Back in the early 1980s, when she was 18 or 19, she loved roller skating so much that everybody called her Skating. So when Mel was sentenced to Bedford, Crooksie immediately made her a monitor of the skating rink. Mel remembers,

She took me under her wing, I felt comfortable with her. A lot of people were scared of her; I’m not going to lie. She was kind of intimidating, like a big bully.

Mel and Crooksie were released at different times, but they spent lots of time together after they were out, and sometimes Mel would drive Crooksie around. Mel tells me that Crooksie helped raise two girls, Diamond and Ebony, the daughters of two of Crooksie’s partners. Crooksie was especially close to Diamond and took care of her since she was a baby, even taught her how to read.

Crooksie bought her Hooked on Phonics. I never seen a child at the age of 2 learning that. I remember she used to call me over to babysit, and I’d have to help teach. Diamond was real smart, very knowledgeable about the world. Crooksie did an excellent job raising Diamond and Ebony. She raised Diamond ’til she died.

Mel remembers something Crooksie said to her when they were in Bedford. They’d been talking about having kids,

and Crooksie told me that they gave her a hysterectomy without her knowledge. I guess it was traumatic for her because she wouldn’t have spoke about it, otherwise. But I thank God she chose me as her friend, because she didn’t have a lot of friends. Like, sometimes people got trust issues.

Mel doesn’t know how Carol Crooks passed. She tells me that Crooksie had had stomach cancer, but it had gone into remission. A few days before her death, Crooksie had complained about shortness of breath, but

they didn’t pay no mind, because it wasn’t the first time she had shortness of breath. She was in the house by herself when she died.

According to an online notice from the Montero Funeral Home, the “final resting place” of Carol Jean Crooks is at the Linden, NJ Crematory.

Maybe someday someone will write a book about Crooksie, rescue the facts from obscurity, make her a star. But history can never know all that makes up one human life; no one can set that down, not ever. Once, author and activist Tillie Olsen wrote a short story called “I Stand Here Ironing.” In it, a mother is talking to a social worker, trying to explain how poverty and chaos had forced her to forsake her daughter. Finally, she looks over all the wonderful things that her daughter might have had, and says:

Let her be. So all that is in her will not bloom—but in how many does it? There is still enough left to live by.

Afeni, Tupac, Huey, Che…all the icons we think we know from history? They’re ghosts who have moved on. But we obscure, noniconic people—we’re still here for each other. Mel and Roz and Diamond and Ebony and all the good people living who knew Crooksie are still a part of her. They carry her on. As Mel says:

She taught me to have a voice: Don’t be afraid to fight for what I want, don’t be afraid to speak. And now I speak, I teach people. I found my voice.